John Deak, a Notre Dame associate professor of history, has won a collaborative research grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities for an ambitious research project that seeks to reshape perspectives on how and why the Habsburg Empire collapsed after World War I.

Partnering with historian Jonathan Gumz of the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, Deak’s three-year grant will support significant archival work across Europe as the scholars explore how the wartime imposition of martial law crushed local political authority and ultimately wiped a 600-year empire off the map.

“This collaboration is full of boldness, and this grant makes all of it possible,” Deak said. “Without it, we’d just be writing about a smaller part of the empire, which is what is normally possible. To write about this monarchy as a real state, falling apart, requires a lot of travel, and we’re grateful for the NEH allowing us to do that.”

Encompassing Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Slovakia, and other Eastern European nations, the Habsburg Empire dated back to the 13th century but came to an end after its defeat, along with Germany and Turkey, in World War I.

For decades, Deak said, the conventional historical narrative — including school texts, both in the U.S. and even in former Habsburg Empire countries — has been that the Austrian-Hungarian system of government was rife with internal conflict and on its last legs by the early 20th century, and the war was simply the strong wind that blew the crumbling house down.

“This collaboration is full of boldness, and this grant makes all of it possible. Without it, we’d just be writing about a smaller part of the empire, which is what is normally possible. To write about this monarchy as a real state, falling apart, requires a lot of travel, and we’re grateful for the NEH allowing us to do that.”

Deak and Gumz, however, believe the empire was not doomed to fail — except for a fatal flaw in the constitutions of its member-states allowing a wartime declaration of emergency and military takeover of the court system. As the empire went to war, the military began trying civilians and local officials under martial law in order to eliminate opposition or settle petty political scores.

“When you disrupt politics, you disrupt the means by which people can talk to one another and work things out — and the military had extreme ideas about how things should be run and forced voters back in a box where they just follow orders,” Deak said. “Austro-Hungarians put the state in the hands of the military, which even bullied the emperor and essentially overran him.

“What the military did while they were in control of much of civilian life actually delegitimized the constitutional state in many corners of the empire. These are important facets of the experience of the First World War that need new attention paid to them.”

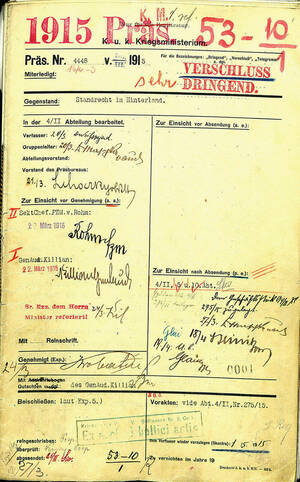

To get a better sense of the impact that the military takeover had on public life, Deak and Gumz will explore archives in several of the successor states of the former Habsburg Empire. Public administration and court records from the time, many still sealed and not opened for nearly a century, were scattered far and wide after the empire fell. Poland, for example, requested all documents relating to the administration of the provinces that became part of Poland after the war.

Knowing where documents like these are and how to find them has been part of the fun but also the difficulty of doing research on this subject, Deak said.

Military files, court decisions, and planning documents will give the historians a better sense of where these emergency wartime laws came from, how they were implemented, and what happened when civilian officials tried to object and push back.

In some cases, opponents were conscripted and sent to the front lines. In others, a protracted battle ensued between civilian officials, local politicians, and their military counterparts. All of it was disruptive and added to the already significant sacrifices the peoples of the empire made to the war effort.

The research pair are dividing up the record-hunting based on the languages they know or can learn — Deak reads Czech and Polish and is brushing up on his Italian. Beginning in May, he will spend as much time abroad as EU visa regulations and COVID-19 protocols allow.

The initial phases of Deak’s research project were supported by grants from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts and the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. That funding allowed him to spend eight weeks getting a sense of what records exist in archives in Vienna, Ljubljana, Warsaw, Innsbruck, and Trieste, where he will now return for longer and more focused research.

As Deak and Gumz seek to disrupt and reframe the modern understanding of the Habsburg Empire in a new book and journal articles, their research also offers an opportunity to shed new light on the civilian-military relationship — a tension Deak says has plagued countries throughout the 19th and 20th centuries across multiple continents.

“This is a story about what happens when a constitution is suspended and the military is given sweeping control of the administration of justice, of people, and of police,” Deak said. “It’s amazing how this stuff can happen in a constitutional state — and even a lot of people who work in this area will think what we’re finding is incredible.”

“This is a story about what happens when a constitution is suspended and the military is given sweeping control of the administration of justice, of people, and of police. It’s amazing how this stuff can happen in a constitutional state — and even a lot of people who work in this area will think what we’re finding is incredible.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on March 28, 2022.